In an earlier post I approached the subject of Autism, Genetics, and Evolution from the perspective of the requirements imposed by alleles and the theory of evolution. This post is an attempt to approach the subject from a different perspective, i.e. the evolution of the brain. My last post discussed autism and minicolumns, suggesting that a) ASD has a minicolumnar underpinning, b) this underpinning is required (i.e. no narrow minicolumns means no ASD), c) it originates in the first 40 days of fetal development (i.e. it is not itself acquired post-natally), d) that this difference falls within the normal range (i.e. that having it does not ‘cause’ a diagnosis, although it may very well result in diversity of thought and cognition, i.e. neurodiversity), e) that something else is therefore required (with no significant speculation as to what that something else may be, other than to generically label it as a ‘second hit’), and f) that research needs to prove or exclude causality among the population of the vulnerable, i.e. proving that something does not cause ASD in those who are invulnerable does not prove that it does not cause ASD in those who are vulnerable. This post builds upon the minicolumn post.

Dr Casanova also provided me with a copy of a work in progress on brain evolution and minicolumns (Casanova - Big Brains Manuscript, in preparation for submission), which has some interesting implications for autism, and prompted me to do some further reading. The same caveat applies as in my last post: I’m attempting to post about some of his work and add what I consider to be some of the implications. As before, bear in mind that I am not a neuroscientist, and as such there is the definite possibility that I have misinterpreted some of the ideas and findings. As such, any errors are mine. In addition, any implications beyond those explicitly stated in Dr Casanova’s research papers should not be attributed to Dr Casanova unless specifically noted.

Brain Size and Structure

A logical starting point in evaluating brain evolution is encephalization, or brain size. Statistical models have been built that compare body vs. brain size across species, from which one can derive an ‘expected’ brain mass based on body size. The actual brain mass divided by the expected brain mass yields an encephalization quotient (EQ). A result higher than one indicates a larger than expected brain mass, while a result less than one indicates a smaller than expected brain mass.

EQ is important as it allows for comparisons of brain sizes across species by automatically adjusting for body size. Larger animals would be expected to have larger brains, and elephants and some whales do have larger brains than humans. But after adjusting for body size, humans have much larger brains than other species. Using an EQ measure based on encephalization of insectivorous primates, humans have an EQ of 28.8, and there is a large gap between modern humans and all non-human primates, including the great apes (our closest relatives). This large gap is filled by the increasing encephalization of prehistoric hominid ancestors.

Encephalization has not affected all parts of the brain equally. The neocortex has been the primary beneficiary of this trend:

"The enlargement of the brain is not proportional; that is, all parts do not develop at the same rate. The neocortex is by far the most progressive structure and therefore used to evaluate evolutionary progress" (Stephan, 1972, p 174)

And Dr Casanova writes (Casanova - Big Brains Manuscript):

"It is the areal expansion of the isocortex and its connections that is ultimately responsible for primate encephalization. Ultimately, the simple addition of minicolumns is sufficient to explain cortical expansion, increased gyrification, and the subsequent parcellation and re-optimization of functional neural networks."

As brain size increases, connectivity requirements also change. Increases in cognitive capabilities may not result simply from increasing brain size or adding minicolumns, but rather, may be a function of brain connectivity. A key requirement for the brain is to generate a network of connections allowing for stable information processing while minimizing conduction and wiring costs. Connectivity is ‘expensive’ in terms of energy required to build and maintain connections. Bigger brains require both more connections and the interconnection of distant locations. Longer connections can result in signal delay/attenuation, and increase the probability of something going wrong. Increasing physical distance also raises the costs of connectivity, as the amount of energy required to maintain connections over longer distances is significant.

The answer to this connectivity issue appears to be at least threefold: modularization, gyrification, and parcellation.

By arranging neurons into minicolumns and driving connectivity between minicolumns, connectivity costs are reduced. Further organization of minicolumns into macrocolumns and then parcellation into functionally differentiated cortical regions also reduces overall connectivity requirements. The net effect is to allow a large number of cells to be connected by fewer axons and in more short-range connections.

Gyrification, i.e. the ‘folding’ of the cortex, reduces the physical distance between different areas and therefore the length of interconnecting fibers. Think of a piece of paper with two dots on it. The absolute distance between the two dots decreases as the paper is folded and the two dimensional surface in effect becomes three dimensional. Only one third of the human cortex is exposed to the surface, with the rest being found within sulci. Increased gyrification also increases the ratio of short range versus long rang connections within the brain.

Encephalization also results in an increase in parcellation of the brain into functionally differentiated cortical regions. Connectivity does not scale absolutely with brain size. As Dr Casanova writes: "increasing numbers of minicolumns impose a connectivity constraint, as non-adjacent or near-neighboring minicolumns become isolated by physical distance. Increasing distance limits connectivity as the amount of energy required to generate and maintain long-distance connections is substantial." Parcellation reduces the need for long distance connectivity by concentrating functions within locations. As encephalization increases, so does the amount of white matter dedicated to local connections. The result is a brain that is "not as equally densely connected relative to a smaller brain."

Within primates the corpus callosum, which connects the right and left hemispheres, generally becomes relatively smaller as isocortex size increases. As Dr Casanova writes, "Interestingly, at a gross anatomical level, perhaps the most obvious manifestation of increased parcellation is that the two cerebral hemispheres tend to be less densely interconnected and more independent." Connections between more distant regions are still required, and these may be maintained through specialized neurons, e.g. spindle neurons. As encephalization increases parcellation and decreases and/or channels connectivity into communication between larger units, there appears to be a corresponding increase in the number of spindle neurons to maintain functional communications.

The Costs of Encephalization

The human brain is expensive to build and maintain from an energy and nutritional standpoint. Kleiber’s law expresses the relationship between body mass and body metabolic requirements, i.e. resting metabolic energy requirements (RMR), also known as basal metabolic energy requirements (BMR). The equation is:

RMR = 70 * (W^0.75)

where RMR is measured in kcal/day, and weight (w) is measured in kg.

Mammalian brain size also scales with body mass, according to the formula:

E = 1.77 * (W^0.76)

where E is brain mass in grams. The similarity in the two exponential scaling coefficients is significant, implying that brain size and RMR are related, and a further inference is that the size of an individual’s brain is closely linked to the amount of energy available to sustain it (Foley and Lee, 1991).

While the brain is about 2.5% of our body weight, it accounts for 22% of our resting metabolism (Leonard and Robertson 1992, p 186). This is in sharp contrast to anthropoid primates using approximately 8% of resting metabolism for the brain, and other mammals using 3-4%. In contrast though, total human resting metabolism does not differ significantly from that of other mammals. So the question is, where does the metabolic energy to grow and sustain the human brain come from?

The answer is the ‘Expensive Tissue Hypothesis’, posited by Aiello and Wheeler, 1995. Aiello and Wheeler analyzed the ‘expensive’ (in terms of metabolic energy) organs in the body - the heart, kidneys, liver and GI tract – noting that together with the brain they accounted for the major share of total body BMR. Comparing the expected vs. actual size of these organs for an average 65 kg human, they found that there were significant differences in actual vs. expected size for both the brain and the gut.

They wrote (Aiello and Wheeler 1995, p 203-205):

"Although the human heart and kidneys are both close to the size expected for a 65-kg primate, the mass of the splanchnic [abdominal/gut] organs is approximately 900g less than expected. Almost all of this shortfall is due to a reduction in the gastrointestinal tract, the total mass of which is only about 60% of that expected for a similar-sized primate. Therefore, the increase in mass of the human brain appears to be balanced by an almost identical reduction in the size of the gastrointestinal tract…

"Consequently, the energetic saving attributable to the reduction in the gastrointestinal tract is approximately the same as the additional cost of the larger brain. "

Since the heart, kidneys and liver cannot be significantly reduced in size, due to their critical functions, to keep BMR at the expected level the higher energy costs of encephalization must be met by the gut. The implication for humans is that there had to have been an increase in dietary quality – e.g. more easily digested food, and the liberation of more energy/nutrients per unit of expended digestive energy - to allow for both a smaller gut and the reallocation of energy to encephalization.

Further evidence for the link between diet and brain size comes from the recent (in evolutionary terms) decrease in brain size in humans. Ruff, Trinkaus, and Holliday (1997) found that the human EQ reached its peak approximately 90,000 years ago, and has since remained fairly constant. But, absolute brain size has decreased by 11% since 35,000 years ago, with most of this decrease (8%) coming in the last 10,000 years. EQ has remained relatively constant because of an equivalent decrease in body size during the same timeframe.

So, what happened? The most plausible interpretation is that EQ is a genetically governed trait, and should not have changed materially in the last 10,000 years. This period has also seen the greatest social/cultural progress in human history, suggesting that the change is not the result of evolutionary selective pressure. Instead, the most likely change has been one of a shortfall in meeting nutritional requirements, in the form of one or more limiting factors preventing the body and brain from achieving their maximum potential development. The most obvious change in this period was the introduction of agriculture (i.e. the agricultural revolution), accompanied by a large rise in grain consumption and a significant drop in animal consumption (from perhaps 50% of diet to 10% in some cases).

The issue is presumably not caloric. Instead, the most plausible current hypothesis is that the decrease in animal consumption resulted in a consequent shortfall in consumption of preformed long-chain fatty acids (Eaton and Eaton 1998). For optimal growth the brain is dependent on the fatty acids DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), DTA (docosatetraenoic acid), and AA (arachidonic acid), which constitute over 94% of all HUFA (highly unsaturated fatty acids) in human and mammalian gray matter (Eaton et al 1998). Neuronal membranes are composed of a thin double-layer of fatty acid molecules. Loss in DHA concentrations in brain cell membranes correlates to a decline in structural and functional integrity of this tissue (source).

There is some evidence that humans are not able to synthesize sufficient levels of EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid – another omega-3 fatty acid) or DHA from precursor alpha-linolenic acid (LNA), and thus must get these EFAs from their diet. An impaired ability to synthesize EPA or DHA would increase the dietary dependence. All of the above are far more plentiful in animal foods than plants. Analysis of likely EFA intake during prehistoric times under a wide range of assumptions suggests that levels of EFA would have been sufficient (0.9g/1000kcal) to allow brain expansion and evolution (Eaton et al 1998). As the human diet changed, our access to these essential fatty acids declined.

Eaton et al 1998 discuss the differences in Paleolithic vs. current dietary EFA consumption, comparing a composite ‘diet of evolutionary adaptedness’ or DEA to current EFA intakes. Prior to the agricultural revolution, human consumption of DHA is estimated at 270 mg/day, while AA consumption is estimated at 1810 mg/day. Current estimates for Western diets are 80 mg/day and 100-1000 mg/day respectively, and the discrepancy for DTA is assumed to be similar. Paleolithic C18 PUFA consumption is estimated at nearly 21.5 g/day, with LA (linoleic acid) at 8.84 g/day and LNA (linolenic acid) at 12.61 g/day, with an overall omega 6:3 ratio of 0.70 in the C18 category. Current Western consumption is LA at 22.5 g/day and LNA at 1.2 g/day, with a total omega 6:3 ratio of 16.74. The result is a massive variation from EFA consumption during the period of peak human brain size, and may result in a shortfall in availability of key EFAs. Why does this shortfall matter?

As Cordain et al, 2001 explains, all mammalian brain tissue appears to have an invariant requirement for DHA and AA, without which normal neural function cannot occur: "Limitations to the supply of either one of these fatty acids will determine limitations to brain growth." They also indicate that the supply of these EFAs is constrained by the limited ability of the liver as well as other tissue to synthesize these fatty acids from their dietary precursors (LNA and LA). As such, we must consume the EFAs we need to build brain tissue. As the authors state: "Encephalization quotients decrease with increasing body size because there literally may be insufficient long chain fatty acid product (AA and DHA) to build more brain tissue."

To add a further note, while the researchers above have concentrated on the implications of EFA changes in our diets, it is also reasonable to assume that the changes in diet with the agricultural revolution would also impact access to other key nutrients, minerals, and even essential and conditionally essential amino acids, as discussed here. Access to zinc, iron, taurine, natural Vitamin A (as distinct from beta carotene) and B12 are some of the nutrients that would have been significantly impacted by the change in diet, although these changes have not been explored to nearly the same extent as the EFA issue. This is not to comment on the implications of these changes or to suggest any consequences or causality, other than to note that they exist and may have implications beyond those discussed in this post.

The increased cost of encephalization has also had another consequence for human development – delayed maturity. As part of their analysis, Foley and Lee, 1991 compare the development of human and chimpanzee brain growth patterns. Chimpanzees are born with a brain mass that is 47% of adult brain mass, and adult size is reached by four years of age. Humans, in contrast are born with brain masses that are 25% of adult brain mass, and by four years old have reached only 84.1% of adult mass. Despite a slower maturation, human daily brain energy costs start at twice those of chimpanzees, and by age five are 3.3 times higher. Growth costs are also commensurately higher.

Foley and Lee suggested that “Mothers from a variety of primate (and other mammalian species) have a goal of weaning infants at an optimal mass, ensuring those infants’ survival, and themselves producing again.” They theorize that the reason for delayed maturity in humans was an inability to sustain both higher brain energy costs and high rates of brain growth, leading to evolutionary selection for the energetically less demanding strategy of increasing the duration of human growth and maturity. Despite a higher DQ and increased foraging efficiency (through increased socialization and cooperation over time), human brain energy costs were sufficiently high to force a slowdown in the rate of growth, despite the cost of reducing female lifetime reproductive rates. Larger brains forced slower growth rates and delayed human maturation.

Brain Evolution and Autism

The evolutionary factors described above have some implications for autism. First, as I stated in the prior post, analysis has determined that minicolumns in the brains of autistic individuals tend to be smaller in size, although with the same total number of cells per column (Casanova et al, 2002a and Casanova et al 2002b). Given that autistic brains tend to be larger than average, the results indicate that autistics also have a higher number of minicolumns. In addition, the neurons within these individual minicolumns tend to be reduced in size. Reduced minicolumn width appears to be a prerequisite for autism. But, the reported minicolumn widths found within autistic brains are still within the normal distribution of minicolumnar width, albeit at the tail end (Casanova 2006). For lack of a better term, I’ll refer to this as a ‘pre-autistic brain’, i.e. meeting the structural requirements for idiopathic autism but not qualifying for an ASD diagnosis (perhaps the broader autism phenotype or BAP?). I’ll also assume that the pre-autistic brain neurons are also of reduced size, for reasons that I will discuss below.

Studies have also shown a postnatal acceleration in brain growth in autistics, resulting in increased brain volume in autistic children vs. controls (e.g. Redcay and Courchesne, 2005), Aylward et al 2002, among others). As per Hazlett et al, 2006, "Significant enlargement was detected in cerebral cortical volumes but not cerebellar volumes in individuals with autism. Enlargement was present in both white and gray matter, and it was generalized throughout the cerebral cortex. Head circumference appears normal at birth, with a significantly increased rate of HC growth appearing to begin around 12 months of age. CONCLUSIONS: Generalized enlargement of gray and white matter cerebral volumes, but not cerebellar volumes, are present at 2 years of age in autism. Indirect evidence suggests that this increased rate of brain growth in autism may have its onset postnatally in the latter part of the first year of life." Thus the autistic brain appears to have more minicolumns, more neurons generally, and appears to grow faster than NT brains.

Given that encephalization appears to result from the addition of more minicolumns, with a resulting increase in gyrification and parcellation, could a more densely packed autistic or pre-autistic brain be a continuation of this evolutionary trend? If so, then the adaptations related to encephalization would also be expected to increase, e.g. increased gyrification and altered parcellation. This appears to be the case. Hardan et al 2004 reported an increase in left frontal gyrification in autistic children and adolescents compared with controls. Herbert et al 2004 reported differences in the parcellation of white matter (Casanova - Big Brains Manuscript), as well as increases in cerebral white matter (Herbert et al, 2003). More minicolumns require more connectivity, requiring more white matter, increasing total brain size, and increasing the bias toward local over global connectivity. The smaller neuronal size within the autistic brain would further reinforce this local connectivity bias.

It may also be noteworthy that the larger than average brains of autistic individuals have consistently shown smaller corpus callosi. Basically, a 'pre-autistic' brain is potentially a more cell-dense brain that may have advantages but is less robust. The addition of more minicolumns could explain the larger brain, increased gyrification, and some variations in parcellation, all within the normal range (albeit at the tail end of the distribution curve), and all of the above would help explain an increased preference of this brain for local over global processing (continuing the encephalization-linked trend), even without any further impact that would tip this still non-autistic brain into ASD (hence the term 'pre-autistic').

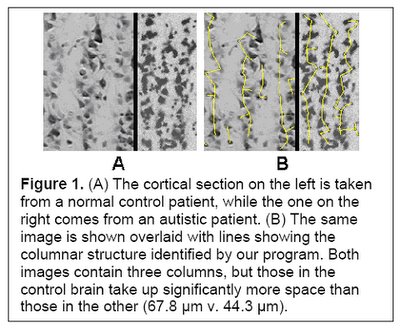

I would hypothesize that this pre-autistic brain is another variation along the path of increased encephalization, created by genetic lottery to either survive and reproduce - if this 'model' ultimately has an absolute advantage or niche advantage - or wither if it does not. Could more minicolumns - but of narrower width - and more neurons but of reduced size be a 'normal' tradeoff related in part to metabolism and limits in connectivity and skull size? Larger neurons would have higher metabolic requirements, so smaller neurons might be a response to a resource constraint (i.e. they might have been larger if the resources to grow and sustain them were available). If the same number of minicolumns and neurons were of 'normal' size then this might also unduly strain connectivity and metabolic demands (connectivity over increasing distance results in increased metabolic requirements) and skull size past any reasonable limits (e.g. an increase in minicolumn width from 44.3 um to 67.8 um as per Figure 1 below would be a 53% increase). In this light, the pre-autistic brain can be viewed as an evolutionary attempt to increase the size of the brain within existing resource constraints.

(Figure 1 Source – TMS Research proposal in preparation for submission, pg 2, with permission)

I would suggest that another reasonable hypothesis is that the pre-autistic brain could strain the nutritional capabilities of the body. If a normal brain constitutes 2.5% of body mass and accounts for 22% of BMR, (Wikipedia suggests that the developing infant brain consumes around 60% of the energy used by the body), then how much more would a larger and faster growing brain tax the metabolic system? Presumably a smaller neuron would require less energy or nutrition than a larger neuron, but I would suggest that the relationship is not linear, e.g. a neuron twice as large would require less than double the resources (in the case of the BMR, the exponential coefficient is 0.75, and it might be reasonable to expect something similar at a cellular level).

To the best of my knowledge it is an open question as to whether a pre-autistic brain also grows faster than average. A hypothesis is that the difference between the autistic and pre-autistic brain is the difference in growth rates. As stated in Courchesne, Redcay, and Kennedy 2004, “Head circumference, an accurate indicator of brain size in children, was reported to jump from normal or below normal size in the first postnatal months in autistic infants to the 84 th percentile by about 1 year of age; this abnormally accelerated growth was concluded by 2 years of age. Infants with extreme head (and therefore brain) growth fell into the severe end of the clinical spectrum and had more extreme neuroanatomical abnormalities.” Could increases in severity be a consequence of brain growth outstripping the required resources?

If autistic children have an increased rate of brain growth in the first few years of life then presumably this imposes a metabolic strain over and above the brain growth of NT children. Since no growth is ‘free’, this metabolic strain (energy and nutrients) must be somehow accounted for, either via an increased BMR, a reallocation of resources within the body, substitution (e.g. a deficiency in omega 3 EFA is compensated for by omega 6 EFAs, but at a functional cost), or through structural or operational deficiency. From Cordain et al, 2001 Fig. 2. “(Log-to-log chart of the resting metabolic rate of 20 anthropoids (new and old world monkey, apes and humans) relative to the predicted relationship based upon the Klieber equation)”, it is apparent that the actual to predicted BMR relationship is very close. I would suggest that BMR is a measure of efficiency that has been very tightly honed as a measure of evolutionary fitness (too low a BMR would result in energy constraints, while too high a BMR would increase the risk of starvation), and there is no reason to presume that autistics would vary significantly from non-autistics in adhering to expected results. But all of the other options result in potential downstream consequences in either the brain or other tissue.

If a shortfall in EFAs has potentially resulted in a decrease in size of the human brain by 11%, then what effect would the shortfall have on a pre-autistic brain with more minicolumns and an equivalent number of neurons per minicolumn – i.e. a brain with more neurons? Further, the increased rate of growth of the autistic (and pre-autistic?) brain in early childhood would increase even further the strain imposed by a shortage of EFAs. Smaller neurons, with a corresponding reduction in cell membranes and reduced metabolic demands might be a compensatory measure, gaining in metabolic efficiency and enhancing processing speed, the ability to process stimuli that require discrimination, and allowing for more complex information processing via local processing, but at a cost of reduced global processing and a reduction in ‘robustness’.

This tradeoff could still potentially have other consequences. Even with reduced neuronal size, the pre-autistic/autistic brain should presumably still require more energy and more nutrients than an NT brain, especially during the period of early childhood brain growth. If autistics adhere to the efficient tissue hypothesis then the logical tradeoff to satisfy this increased demand is with the GI system. And I would further speculate that another tradeoff may potentially occur with the liver.

Let’s be clear that I’m not suggesting at this point that the all autistic or pre-autistic children have GI or liver issues. What I am suggesting though is the following: a) that the increased brain costs must be met somehow, since no growth is ‘free’, b) that the GI system (and liver) are the logical organs to endure reductions to meet increased brain requirements, and c) that there in some cases may be consequences to this tradeoff in terms of the functional capabilities of these organs and potentially for overall health. In the case of the GI tract, some of these consequences could conceivably result in downstream issues (e.g. immune issues, impaired enzyme production, reduced metabolic efficiency, reduced nutrient and mineral absorption, etc.) that could have other systemic consequences, including consequences for the brain. Note that these issues would not ‘cause’ the brain to become ‘pre-autistic’, but they might have consequences for the pre-autistic brain that might result in an ASD diagnosis. Liver issues too could hypothetically have downstream consequences via a reduction in detox capabilities.

Further, if an NT brain is already facing resource constraints resulting in diminished size vs. potential (i.e. that 11% decrease in size), how much more critical would a GI 'issue' be for a pre-autistic brain? Even if the pre-autistic brain did not result in GI issues, comorbid GI issues might provide an additional resource constraint for a pre-autistic brain that could have a substantial impact on outcome. In this case it is not required that pre-autistic/autistic children have more GI issues than NT children, but rather, that given the increased metabolic demands of a pre-autistic/autistic brain, that the consequences of GI issues might be significantly greater on a larger and more demanding but less robust brain. The rates of comorbidity may be the same (although the efficient tissue hypothesis potentially suggests otherwise) but the consequences might not.

A further implication of the above goes back to the delayed maturity required of human offspring to allow for the management of the higher energy costs of encephalization. Since the autistic (and possibly the pre-autistic) brain is larger than an NT brain during the first few years of life and experiences a higher rate of growth, could delayed maturity be a further adaptive mechanism? Although much of this early growth is driven by connectivity, the increased number of neurons and minicolumns suggests that there is a lot more in the pre-autistic/autistic brain to connect, requiring substantial resources and energy. While this white matter growth is higher in autistics than NTs, it might still be a reduced rate of growth compared to what would be required to maintain an equivalent level of maturation in this larger brain as found in NT children.

Regardless of one’s beliefs regarding autism etiology, I would suggest that there are some serious implications regarding the nutritional status of autistics that flow from this analysis. The evolutionary and nutritional science referred to above is both mainstream and peer reviewed - no DAN! practitioners in sight. While the analysis has some similarities to Children With Starving Brains, the analysis, conclusions and hypotheses presented were arrived at from a different direction. I would suggest that it is a reasonable proposition that the autistic brain, if it is larger in childhood and goes through the growth spurt that mainstream research has detected, would have to face the same resource and energy constraints of NT brains, but with even higher requirements needing to be met. As such, one does not have to believe that addressing autistic nutritional requirements will result in a ‘cure’ to buy into the concept that autism brings with it some increased nutritional requirements, and that autistic brain ‘performance’ might be enhanced by compensatory nutritional intervention. Notice that I have ducked the entire issue of whether some autistic children with compromised diets due to sensory or tactile issues are further compounding any nutritional issues.

Finally, just to throw a hat into the discussion (see the last post’s comments regarding “The Meaning of Life” and hats for context), the above discussion may also offer a hypothesis to explain the ‘epidemic’, i.e. the perceived increase in the number of autistics in the past couple of decades. As mentioned above, absolute brain size has decreased by 11% since 35,000 years ago, with most of this decrease (8%) coming in the last 10,000 years. EQ has remained relatively constant because of an equivalent decrease in body size during the same timeframe. But in the post-WWII period human height has been increasing in the Western world and Asia. If EQ is genetically driven, then as stature increases, is brain size also on the rise? If resource constraints are lessening (perhaps with more variety in the diet, more access to protein, more access to EFAs?), then might constraints on pre-autistic brain size be diminishing along with constraints on human stature in general? Human stature can take at least two generations to recover (your grandmother’s dietary deficits affected your mother and the resources that she could bring to bear during your gestation). What if nutritional quality gains over the past two or more generations are now removing some of the nutritional constraints on pre-autistic brain development and size (i.e. more resources could allow for higher numbers of minicolumns to be generated during that first 40 days)? This might increase the pool of pre-autistic brains, i.e. the brains described above as being vulnerable to ASD.

Just something to think about.

13 comments:

Very interesting Ian. I'll need to re-read this, as it was a lot to "digest" in one read through.

One kink would be the research by Dr. Buitelar (Buittelar?) which should be on the MIND's website on video, which shows that autistic kids don't have large heads if you take into consideration their height. They are BIG kids, he would say. I was a big kid, I'm a tall woman, my sister is taller and she's not autistic.. . hmmm

I'm all for improving the fats in everyone's diet. As far as I know kids who go through famine are not more likely to be autistic, though moms who go through stress, as in a hurricane in Louisiana are more likely to have autistic babies... I think that's a chemical thing, cortisol, not EFA's.

At any rate, it doesn't sound like your hypothesis, which is very interesting, leaves much room for "fixing" the autistic in late childhood or adulthood.

And we don't know if autistics have worse dietary absorbtion overall than typical kids. I think much of the diarrhea etc is down to lack of enzymes for lactose and other dissacharides and stress, stress, stress and stress.

I'm all for long breastfeeding times (like 2 or 3 years), too, for all babies, for lots of reasons. Not that it should be commanded, but that it should be encouraged.

Hi Ian. Extremely interesting post.

I have found several points to comment

On animal models, the locomotor costs seem more brain mass related than the gut size:

Costs of encephalization: the energy trade-off hypothesis tested on birds.

The trade-off between locomotor costs and brain mass in birds lets us conclude that an analogous effect could have played a role in the evolution of a larger brain in human evolution.

Relation of muscle and fat seem to be more brain mass related

Metabolic correlates of hominid brain evolution.

Comparative primate data indicate that humans are 'under-muscled', having relatively lower levels of skeletal muscle than other primate species of similar size. Conversely, levels of body fatness are relatively high in humans, particularly in infancy. These greater levels of body fatness and reduced levels of muscle mass allow human infants to accommodate the growth of their large brains in two important ways: (1) by having a ready supply of stored energy to 'feed the brain', when intake is limited and (2) by reducing the total energy costs of the rest of the body.

Human encephalization and developmental timing.

The "brain allometry extension" theory postulates that the progressive extension of a conserved primate brain allometry into postnatal life was the basis for brain enlargement in the human lineage. This study shows that published primate and human growth data do not corroborate this model. Instead, the unique encephalization of H. sapiens is alternatively described as the result of evolutionary changes in three aspects of developmental timing. The first is a moderate extension in the duration of brain growth relative to our closest extant relatives, contrary to the view that human brain growth is drastically prolonged into postnatal life. Second, humans evolved a derived brain allometry in comparison with chimpanzees and early hominins. Third, humans (and other anthropoid primates to a lesser degree) display a significant retardation in early postnatal body growth in comparison with other mammals, which directly affects adult encephalization in our species. The rejection of the "brain allometry extension" model may require a reevaluation of the adaptive scenarios proposed to explain how human encephalization evolved.

The fatty acids would affect not only nutrition, but also gene expression. Gene expression can be affected surely postnatally.

Nutrition in brain development and aging: role of essential fatty acids.

Essential fatty acids in visual and brain development.

Intracellular fatty acids or their metabolites regulate transcriptional activation of gene expression during adipocyte differentiation and retinal and nervous system development. Regulation of gene expression by LC-PUFA occurs at the transcriptional level and may be mediated by nuclear transcription factors activated by fatty acids. These nuclear receptors are part of the family of steroid hormone receptors. DHA also has significant effects on photoreceptor membranes and neurotransmitters involved in the signal transduction process; rhodopsin activation, rod and cone development, neuronal dendritic connectivity, and functional maturation of the central nervous system.

Nutrition is known to affect brain functioning

Head size and intelligence, learning, nutritional status and brain development. Head, IQ, learning, nutrition and brain

These findings confirm the hypothesis formulated in this study: (1) independently of age, sex and SES, brain parameters, parental HC and prenatal nutritional indicators are the most important independent variables that determine HC and (2) microcephalic children present multiple disorders not only related to BV but also to IQ, SA and nutritional background.

Role of micronutrients for physical growth and mental development

A very complete explanation of the Brain Energy Metabolism

Brain Energy Metabolism

I found this webpage and implications particularly important (as always that I read about the consequences of medication in autistic people)

Brain Research Metabolism The potential role of hypoxya at birth

There are several reports about metabolic imbalances in autism. Some ( a few) of them

Volumetric analysis and three-dimensional glucose metabolic mapping of the striatum and thalamus in patients with autism spectrum disorders

Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a population-based study

Evidence of altered energy metabolism in autistic children

In this pilot study, the authors investigated the hypotheses there are increased concentrations of lactate in brain and plasma and reduced brain concentrations of N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) in autistic children. 2. NAA and lactate levels in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe and the cerebellum of 9 autistic children were compared to 5 sibling controls using MRS. Plasma lactate levels were measured in 15 autistic children compared to 15 children with epilepsy. 3. Preliminary results show lower levels of NAA cerebellum in autistic children (p = 0.043). Lactate was detected in the frontal lobe in one autistic boy, but was not detected any of the other autistic subjects or siblings. 4. Plasma lactate levels were higher in the 15 autistic children compared to 15 children with epilepsy (p = 0.0003). 5. Higher plasma lactate in the autistic group is consistent with metabolic changes in some autistic children. The findings of altered brain NAA and lactate in autistic children suggest that MRS may be useful characterizing regional neurochemical and metabolic abnormalities in autistic children.

Autism and lactic acidosis

Four patients are described who have two coexistent syndromes: the behavioral syndrome of autism and the biochemical syndrome of lactic acidosis. One of the four patients also had hyperuricemia and hyperuricosuria. These patients raise the possibility that one subgroup of the autism syndrome may be associated with inborn errors of carbohydrate metabolism.

Relative carnitine deficiency in autism

The relative carnitine deficiency in these patients, accompanied by slight elevations in lactate and significant elevations in alanine and ammonia levels, is suggestive of mild mitochondrial dysfunction. It is hypothesized that a mitochondrial defect may be the origin of the carnitine deficiency in these autistic children

These last findings also can be related to mio/cytopathyes.

Even more, this kind of findings (News) can be also metabolism-related in modulation in first infancy more than ONLY gene-related.

Hi I found 2 links that did not work. Therefore Here you have them again

1-Brain Energy Metabolism

Very complete analysis of Brain metabolism of glucose, glycolysis and phosphorylation

http://www.acnp.org/g4/GN401000064/CH064.HTML

2-The News

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/6037836.stm

Sometimes these links do not work because of the final needed /for the string of characters.

Sorry.

Ma Luján

Hi Camille,

Thanks for stopping by and for the comment.

I've read that one of the most consistent features of autistics is large head size, but I would agree that that does not preclude bigger body size too (and I'm not sure how many researchers are taking body size into account in their analyses).

Take my daughter as an example. Her diagnosis is ‘autism at the severe end of the spectrum’. At 3yrs 3mos she was 105cm tall, which according to the CDC growth chart here is pretty much off the charts. She also has a large head circumference (not quite as large, but still well above the 90th percentile). I would argue that her example does not invalidate the hypothesis, but in fact might support it. On a brain vs. body size comparison she is not necessarily different from average. But on an age-based comparison she certainly is. And that growth had to be fueled from somewhere, still potentially stretching the limits of what is metabolically possible. Regardless of whether the body keeps up, if her brain jumps from e.g. 50th percentile to 95th percentile and stays at that rate for the first few years it is still growing much faster than average. If the body is keeping up then that is just further strain, since both body and brain growth requirements have to be met.

I would speculate that kids who go through famine would probably be less likely than average to have this issue, since famine should restrict all growth (and potentially damage the brain and the rest of the developing body in other ways). I would suggest that issues might occur instead when there are apparently sufficient metabolic resources but with shortages in key essential nutrients (e.g. DHA or AA) that compromise the resulting growth rather than stopping it.

I’m not suggesting that autistic children have worse absorption than typical kids. Instead, I’m suggesting that dietary issues affect everyone (hence that 11% average brain size decrease from peak). But further, I’m hypothesizing that if autistic children have larger brains that go through a faster growth spurt than average, that the same issues that affect everyone could potentially have a more significant effect on them due to nutritional requirements that are higher than average (more minicolumns with the same number of neurons per minicolumn results in a higher number of neurons that need to be supported, from both an energy and a growth perspective). Brains ‘consume’ resources totally out of proportion to their percentage of body mass. In the case of your sister, she might have been bigger than you, but if she did not have this ‘pre-autistic’ brain structure then the consequences of being taller (and did she grow faster or over a longer duration? - slower growth puts less of a metabolic strain on the body) might not have been as great.

Also, to be clear, I’m not suggesting that this is the only cause of autism. Instead, I’m hypothesizing that a bigger 'pre-autistic' brain and faster growth would stretch metabolic limits and potentially have serious consequences, and that for those who also have GI or other metabolic issues that these issues could have even more of an impact than they would have on NT kids.

I totally agree with you regarding the fats in everyone's diet. The various papers have given me some food for thought (no pun intended). I'll confess to starting to take a couple of CLO capsules each day to get some of my required EFAs, and to taking other steps to correct my errant ways (going slowly - Rome wasn't built in a day). It shouldn't come as a surprise to anyone that the Bear has been taking a measured dose of CLO for quite a while now (she actually seems to like it - no, really!), as well as other EFAs.

Quite interesting -- it's folk wisdom that "fish is brain food," and the research does indeed seem to support that.

It makes sense to me that if a child does not get enough EFAs in his or her diet, a fast-growing brain would take most of them, leaving insufficient amounts for other parts of the body. That would explain not just gut problems, but also other issues that seem to be fairly common in the autistic population, such as eczema.

I never could get my son to take CLO capsules (or any kind of pills), but I noticed that when he ate salmon regularly, his eczema disappeared. Apparently he needs a large amount of EFAs in his diet, otherwise he can't make enough natural skin oils to keep his skin healthy.

He also has the body type you and Camille mentioned: tall, skinny, fast metabolism, big head.

Hi María Luján,

Thanks for the comment.

I’m not quite sure if I agree with the first link. The Costs of Encephalization examines the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis in relation to birds, but I’m under the impression that the hypothesis relates specifically to mammals, and especially (but not exclusively) to primates. That has been the context in which I have seen it discussed. It makes sense to me that birds would be governed by a similar BMR to body mass equation as other animals, but I would suggest that their different brain structure (I’m not sure that birds have minicolumns, which may imply a different energy cost to 'bird brains' ;-) ) and their reproductive method would be key differences.

I would agree with the Metabolic Correlates of Hominid Brain Evolution (Leonard et al 2003) paper that greater body fat and reduced muscle mass, especially in infants, would assist in conserving energy and resources to support encephalization. I don’t see this as contradictory to the Efficient Tissue Hypothesis but rather as supportive of the need for accommodation of the brain’s requirements, fitting in well with the direction of the third link.

The Human encephalization and developmental timing paper (Vinicius 2005) is an interesting one. My understanding is that he is suggesting a "combination of proportional prolongation of brain growth, distinctive brain allometry, and reduced rates of postnatal body growth" rather than just delayed brain growth. While this may not be in agreement with Foley and Lee, 1991 in terms the particular method of evolutionary selection employed (i.e. distinctive brain allometry vs. selection for ‘mere’ delayed maturity), the net result is the same in terms of slower development in humans than in other primates and in primates as a group compared with other mammals. I’m probably oversimplifying the difference in approaches as one of ‘how did this evolve’ rather than ‘what happened’, in that I believe Vinicius also agrees that delayed human maturity was a requirement to allow sufficient energy for brain development, but extends this into a more ‘whole organism’ rather than a brain-centric approach.

I guess that it will take some time for anthropologists to reach the same level of explanation, understanding, and agreement as we find in the world of autism.(sigh) ;-)

BTW, I quite liked the Singh paper (Role of micronutrients for physical growth and mental development) and the Nutrition in brain development and aging paper, and the others I looked at were interesting too. Thanks.

Hi Bonnie,

Thanks for stopping by. One of the interesting things to me about this line of thought is that this is something that presumably most of us (ND and interventionist, and everyone in between) can hopefully agree on, i.e. regardless of why one is intervening, that there are some benefits to autistics (and indeed for everyone) in better nutrition. While it is something that many generally overlook or pay little attention to (unfortunately I'm known by name in more than a couple of fast food outlets), the evidence suggests that the consequences of our lack of attention are more significant than we realize.

I also find it interesting that much of this research is being conducted by anthropologists and nutritionists. Where are the neurologists in this, esp. since some of this research dates back a decade or more?

Hi Joseph,

Thanks for dropping by and for the comment.

The Sotos syndrome example is interesting (I can always count on you to add an interesting parallel example – to be clear, that’s a compliment). One of the things I noted was the number of similarities between Sotos syndrome and some of the suggested comorbidities of autism.

You wrote: "I don't think it's just the extra energy required for a bigger brain. If the number of neurons is greater, that must affect learning speed and rigidity of thought."

I agree. I suggested that delayed maturity might be an adaptive mechanism and that more neurons would result in more to connect, straining resources, but I would also agree that the sheer increase in complexity would also be a contributing factor.

I also agree with the ‘very long’ statement. The post started out as an extension of the minicolumns post, exploring the idea of autism as an extension of the evolution and encephalization trend. But Dr Casanova also referred to the extensive tissue hypothesis, and when I went off exploring this tangent I came across a lot more info on the the brain growth-energy and brain growth-EFA relationships. The potential connection to autism popped into mind, followed by the link to the delayed maturity hypothesis of Foley and Lee, and the result was a collection of 5126 words to inflict on any unsuspecting readers who might wander by or be lured in.

Hi Shawn,

Thanks for the slogging through all of that and for the nice comment.

Regarding: "Are you sure you're not a neurologist?"

Yes. Some have stated that I'm not a brain surgeon either. ;-)

I would say in fairness to neurologists and other scientists and researchers that I have no professional reputation to protect, and therefore I can speculate - and put it in writing - while some cannot do so without potentially exposing their reputations to risk. Having said that, I'd also like to clearly state that the implications in these posts beyond those stated in other papers are my thoughts (although building on others' good work), not someone else's trial balloons.

Hi Ian, I am going to have to read this a few more times as I am just a "regular mom" of a child with autism. However, if I am grasping at least part of this, I believe I have come across the first post that mirrors my own view (however simplified by comparison) of autism as it relates to evolution. I did not know the science behind my thoughts (still trying to grasp). Let me just throw something else out there. How might high-powered, prescription vitamins play a role in the developing fetus? Could certain genes get "turned on" by a steady flow of super-powered vitatmins, as if mother nature were saying "hey, let's prepare for an individual who is no doubt going to be able to rely on this great nutrition to support brain growth." I could not breast feed and I know that the formulas were intolerable to my little one. Also, has anyone explored the effects of our technological world on the evolution of human kind? By this I mean that our survival skill set has changed drastically over the last 100 years. Our own need for community socialization has sort of morphed into staring at a computer screen, posting (or reading) a blog... not much vocalization going on here. I certainly do not understand how genes get mutated or turned on/off, but I do know that no other time in the history of human kind have we seen such technological advances as in the past 100 years. I could go on and on, but I feel I am out of my league intellectually here and don't want to bore anyone!

Hi Theresa M.,

I apologize for not replying earlier (I only just saw the comment). I certainly think that access to better nutrition may have a developmental impact, and it is well within the realm of speculation that improved access to vitamins may be part of this impact.

Regarding the impact of technological change, I'd suggest that the changes may have been too recent to have impacted our genes, but the changes could certainly have changed which genes could be considered favourable vs. unfavourable in this environment.

Hi,

Norman Geschwind and Simon Baron-Cohen have two important pieces of the puzzel. Central to understanding the etiology of autism is understanding heterochonic theory, specifically neoteny, and how sexual selection informing social structure juxtaposes with heterochonic theory.

Please consider visiting http://www.neoteny.org/?cat=7 to review a unique and unorthodox theory for the cause of autism.

Thank you,

Andrew Lehman

Post a Comment